Further references and links

In the course of writing the book we endeavoured to take into account most of the relevant publications that were available up to January 2023, adding Bevins et al. (2023) to the list at the last-minute. We intend to update this page from time to time to highlight more recent publications that may be of interest.

This page also includes some further discussion of points raised in the book and by our readers.

Recently published research

Dating Woodhenge

- The report on radiocarbn dating and chronological modelling of charcoal samples and antler picks from Woodhenge, as described on pp. 88–90 and listed as “Amanda Chadburn and Peter Marshall, forthcoming” in the book, has now been published as Historic England Research Report no. 94 (2024) and is freely available on-line.

- The full reference is Marshall, Peter, Amanda Chadburn, Irka Hadjas, Michael Dee and Joshua Pollard, Woodhenge, Durrington, Wiltshire: Radiocarbon Dating and Chronological Modelling. Portsmouth: Historic England (Research Report Series 94/2024).

“Missing data”

- This paper, listed as ‘in press’ in the book, has now been published in the journal Cosmovisiones/Cosmovisões. It focuses on monuments in the Stonehenge landscape, summarising modern ideas about these monuments and their astronomy, critiquing certain recent theories, and discussing some open questions.

- The full reference is Ruggles, Clive and Amanda Chadburn 2004 ‘Missing data’. Cosmovisiones/Cosmovisões, 5(1) (2024), 99–109. Available on-line at doi.org/10.24215/26840162e007.

Provenance of the Altar Stone (p. 66)

- A paper published in Nature in August 2024 provides geochemical evidence that the Altar Stone did in fact come from north-east Scotland, implying that it was transported over 750km.

- Clarke, Anthony, et al. 2024 ‘A Scottish provenance for the Altar Stone of Stonehenge’, Nature 632, 570–590. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07652-1.

Further discussion of some points raised in the book

Skyscape and landscape (p. 17)

- Silva (2015, 2) notes that “the sky is a natural phenomenon that is turned into a cultural skyscape through human agency” but argues that we should not de facto consider the skyscape and landscape together, as phenomenologically they are very distinct. “There is a materiality to the landscape that is of a different nature to that of the skyscape: landscapes are accessible, can be tangibly manipulated; skyscapes only metaphorically or by non-humans” (Silva 2022, 11).

First suggestion of the term ‘ethnoastronomy’ (p. 27, note 13)

- Burrows and Spiro (1953, 95) provide what may be the earliest published suggestion the use of the term ‘ethnoastronomy’, where they describe Maud Makemson as “a pioneer in what might be called ethnoastronomy”. However, it is possible that this remark is reproduced from earlier notes. Goodenough (1953) cites Burrows’ Field Notes from Ifalik, which in his bibliography are said to be “reproduced in the files of Human Relations Area Files, Inc., New Haven” and dated to 1947–8.

Discovery of the lunar orientation of the Station Stone rectangle (p. 72)

- Since the publication of our book, we have been asked a number of times who first discovered the lunar orientation of the longer Station Stone rectangle axis. This is generally credited to C.A. (‘Peter’) Newham in an article published in the Yorkshire Post on 16 March 1963 (see, for example, pp. 34-35 of fellow Yorkshireman Fred Hoyle’s book On Stonehenge (Hoyle 1977)).

- A scan of the original Yorkshire Post article, plus a reprint of the text, are available on-line here. Misleadingly titled “The mystery of Hole G”, this was actually written by a correspondent (Douglas Emmott) about Newham’s work, which was not itself published until 1964 in The Enigma of Stonehenge (reprinted as Newham 1972: see pp. 23-25). By the time Newham’s book came out, Hawkins had published the first “Stonehenge Decoded” article in Nature (26 Oct 1963) (Hawkins 1963), which also included these alignments. Hawkins always insisted he had arrived at his idea independently.

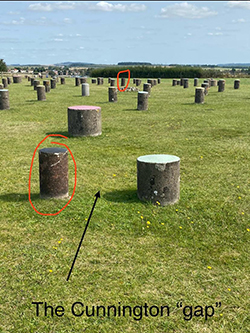

The solstitial axis of Woodhenge (pp. 86–88; fig. 6.4)

- These two photos, taken by AC in August 2024, are helpful in visualising the ‘Cunnington axis’. Both are towards the north-east.

Solstice full moons (p. 116, caption to Fig 7.7)

- As the average length of the lunar phase cycle (synodlic month) is 29.5 days and is uncorrelated with the solar year, it follows that a full moon will occur within 24 hours of the June solstice once in every 15 years or so on average (29.5/2 = 14.75).

- In practice, the moon appears full for a significant period before and after the moment when it is technically full, and the moment of the solstice can occur at any time between the evening of June 20 and the early morning of June 22 depending upon the leap year cycle and other factors. Thus in 2024 the almost-full moon (actual full moon occurred at 02:10 on June 22) rose on the evening following the solstice sunrise (the solstice having actually occurred at 21:51 on June 20) even though the events were technically separated by 28 hours.

- Note that this has nothing to do with the 18-year Saros cycle which, although accurately predicting the occurrence of eclipses, does not preserve the relationship to the solstice because each cycle adds 10/11/12 (+ 1/3) days.

- The table below shows some occurrences of June solstice full moons, calculated using the on-line tools available at stellafane.org. Times are BST (UT+1).

| Year | June solstice (d, h) | June full moon (d, h) | Difference (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 21 13 | 21 14 | +1 |

| 1967 | 22 03 | 22 06 | +3 |

| 2016 | 21 0 | 20 12 | –12 |

| 2062 | 21 2 | 21 23 | +21 |

The cathedral analogy (p. 177)

- Rob Ixer has coincidentally suggested a similar idea in his review of Pitts (2022), published while our book was in press. In his view Stonehenge’s enduring and essential spirit is the ‘cult of carts’, as at Chartres cathedral, where ”citizens ... of all social classes, harnessed themselves to carts like oxen and dragged materials to the building site as an act of mass piety” (www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=2146415184).

Additional references

- Goodenough, Ward H. 1953 Native Astronomy in the Central Carolines. Philadelphia: University Museum, University of Pennsylvania (Museum Monograph, 6)

- Hawkins, Gerald S. 1963 ‘Stonehenge decoded’, Nature 200, 306–8.

- Silva, Fabio 2015 ‘The role and importance of the sky in archaeology: an introduction’, in Silva, F and Campion, N (eds), Skyscapes: The Role and Importance of the Sky in Archaeology. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1–7

- Silva, Fabio 2022 ‘Defining skyscape’, Culture and Cosmos 26 (2), 3–14. doi.org/10.46472/CC.0226.0201

Some additional publications

- Pollard, Joshua 2017 ‘The Uffington White Horse geoglyph as sun-horse’, Antiquity 91, 406–20

- Prendergast, Frank 2023 ‘The meaning of dark, light and shadows: inferences in art, materiality and cultural practices’, Culture and Cosmos 26 (1), 3–32. doi.org/10.46472/CC.0126.0201

Other supplementary on-line materials

Further references and links